My thesis has been consuming most of my time for the last few weeks, so housekeeping has been minimal. However, now that I am in quite a final stage (yikes!) of my thesis, I felt relaxed enough to catch up on things today, including laundry and some potted plants and getting my sewing machine fixed.

Now that my rosemary is happy, I am addressing one of those ‘skills I’d like to acquire’ projects: making sourdough bread.

I never even thought about this until last autumn, when a few things I’d been reading about diet touted the advantages of sourdough bread (more on that below). The rise in sourdough comes not from the usual baker’s yeast but from natural yeasts which occur in grain and are cultivated by fermentation of a ‘starter’. This bubbly flour-and-water mixture is added in small amounts to water, flour and salt to leaven the whole loaf. Now, this appealed to my love of DIY – homemade yeast! But it also made me remember what I know of early American cooking, when sourdough was used for bread and biscuits, and feeling the urge for some ‘living history’ I really wanted to try it out myself.

Short story to tell, I eventually gave up. Here’s what happened. I read multiple sources on how to make your own starter, and followed the directions, mixing small amounts of flour and water, adding to the mixture each day, and watching it become bubbly as the yeasts became active. This part did genuinely work, and nothing got mouldy. I even put it in a nice glass jar and had visions of myself, Homemaker Extraordinaire, whipping up tangy homemade breads every week from now on and forever, living a life of vitality and handcrafted goodness.

The first sourdough loaf I baked did rise a little, but not much. It smelled like strong cheese when it was baking, really a bizarre smell from bread, but I chalked it up to the whole ‘fermentation’ thing. In fairness, it was edible, but very sour and not particularly nice in texture. I ended up slicing it thin, into little rectangles (the loaf was half the height it should have been, so no squares), and toasting it well. It was something akin to melba toast, okay with cheese but pretty tough on the teeth.

After this, I did notice that my starter (which I kept dutifully feeding with more flour and water) changed in smell, turning from sour to pleasantly malty. Taking this cue, I made another loaf of bread. You know what? This one was amazing. It rose, was golden in colour, had a nice soft crumb and a beautiful multilayered crust, and tasted a little tangy but definitely like bread (not strong cheese).

After that, though, a few other loaves turned out very much like the first: sour, acidic, dense. I put my starter in the fridge while we were gone over Christmas, having read that this would slow it down and enable it to survive without feeding for a while, and when we returned home after the break I started feeding it again. But with one thing and another, I forgot about it, it got pinkly mouldy and dry, and I eventually threw it out and decided to start over later. Mike was very glad to see that ‘the evil flour’ was gone; I think its silent, pale, gaseous life of fermentation over by the boiler always creeped him out a little.

Why bother with sourdough?

This brings me to the implicit question – other than historical interest or idle curiosity, why is it worth bothering to make sourdough bread?

There are certain ‘traditional diet’ advocates who say that sourdough bread is not only the most traditional form of bread making, but is the only type you should eat, because the fermentation process breaks down certain ‘anti-nutrients’ in the grains which inhibit your body’s ability to absorb nutrients. This beneficial activity doesn’t happen with modern baker’s yeast because it thrives at a different pH than naturally occurring yeasts in grain, and the right pH is crucial for these anti-nutrients to be broken down. Sourdough bread, the claim goes, is easier to digest and more nutritious because more vitamins are available for your body to absorb.

I actually did some investigation on this at the British Library, and although I’m not aware of any extensive scientific studies, I found two that were interesting. In one pilot study, Celiac’s patients (who can’t eat gluten) were given sourdough wheat bread every day for 60 days. None of them showed any adverse reaction, and the researchers postulated that the sourdough fermentation process rendered the gluten tolerable to their systems.* Obviously this is interesting for those who are gluten intolerant, but it strikes me as particularly interesting given that gluten and grains in general are getting a pretty bad rap these days, some people suggesting that nobody should be eating grains and whatnot. I sort of wonder whether perhaps it’s a problem of needing to prepare the grains properly, rather than avoiding them altogether. Just a thought.

Another study found that certain nutrient levels in grains were elevated after sourdough fermentation, including zinc and B vitamins. (I think I have notes from this article but I’ve lost them, so am not sure of the reference.) Once again, it’s interesting to me that a simple process can render the same food more nutritious.

One other advantage of sourdough bread is its keeping ability. One frustration of homemade bread is how quickly it goes stale and dry; of course commercial breads include additives to help prevent this. Most sources I’ve read remark that sourdough bread stays soft naturally for 3 days, and will last a whole week at room temperature without going mouldy.

You can actually buy proper sourdough breads, though often not at the cheaper supermarkets. I’ve found a couple of varieties at Waitrose that are very tasty, but…usually around £2 a loaf. I have never been fussed about making homemade bread all the time simply because you can buy a cheap loaf (even wholemeal) for about the cost of making it. However, in the case of sourdough, that doesn’t appear to be true. Hence, I decided to try again to make it myself.

Another attempt

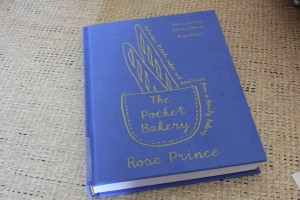

I really recommend this book, which I got at the library. The author won my heart when she started the book with sourdough as the most traditional type of bread, and placed ‘modern [yeast] breads’ in the second section; not that I hate ‘modern breads’, simply that you don’t always find cookbooks with a sense of history.

I made a fresh starter with her detailed instructions, and my first experimental loaf is rising as I type. My ultimate goal is to use wholemeal flour, but I decided to work my way through the book sequentially, beginning with the basic recipe, as a way of giving myself a proper ‘course’ on the subject.

[See this post for an update.]

This looks so good! You’re inspiring me to try … I bake bread often but never quite got my mind around sourdough even though I love the taste. I must try now, thank you!

Well, I’m no expert, but I just baked the loaf after its overnight rise and it turned out beautiful and tasty! So I can definitely recommend that book at least. She does assume a few bits of equipment I don’t have, but I seemed to get by just fine using what I do have.